RESEARCH QUESTION

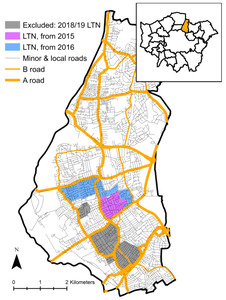

Road traffic injuries are a significant threat to health (Public Health England 2018). Low traffic neighbourhoods (LTNs) are schemes that remove through motor traffic from residential streets using ‘modal filter’ measures such as planters or lockable bollards (Figure 1). By reducing motor vehicle volumes, LTNs are expected to reduce the risk per trip to people walking or cycling (Aldred et al. 2018) - although we know of no empirical evidence. Impacts on absolute injury numbers are less obvious, given evidence that LTNs prompt a mode shift away from cars (Aldred and Goodman 2020; Goodman, Urban, and Aldred 2020), and given that car occupants experience a lower per-mile injury risk than walking and cycling (Department for Transport 2018). It is also important to consider impacts on boundary roads, which may at least initially see some increase in motor traffic, although potentially mitigated by reduced conflict at junctions.

Here we examine how LTNs introduced in 2015 and 2016 by the London Borough of Waltham Forest affected numbers of road traffic injuries inside the LTNs and at the boundaries.

METHODS AND DATA

We used 2012-2019 police injury data (“Stats19”). This gives information on the travel mode and injury severity of road traffic casualties, plus detailed geographical coordinates for the crash location (Department for Transport 2020). Our primary outcome was number of casualties of any severity, both in total and by casualty mode of travel. We present secondary analyses examining killed or seriously injured (KSI).

We focus on LTNs introduced between September 2015 and June 2016. After mapping the boundaries of these LTNs (Figure 2), we assigned all nearby road traffic injuries into two mutually-exclusive LTN groups:

-

Injuries inside the LTN, defined as injuries at least 25m inside the LTN boundary, and not recorded as being at the intersection with a boundary road.

-

Injuries at the LTN boundary, defined being located from 25m inside to 50m outside the LTN boundary.

We made pre/post comparisons of injury numbers in these LTN groups between January 2012-August 2015 (‘pre’) versus July 2016-December 2019 (‘post’). We compared trends in these LTN groups to trends in injuries elsewhere in a) Waltham Forest and b) Outer London using Fisher’s exact chi-squared tests. Injuries in parts of Waltham Forest that became an LTN in 2018/2019 were excluded (both pre and post) from comparisons (Figure 2).

As there were no A (primary) or B (distributor) roads inside our LTNs[1], we compared injuries inside the LTNs with comparison group injuries excluding A or B roads. We compared injuries at the LTN boundaries with comparison group injuries on any road type, but confirmed that our findings were very similar when restricted to injuries on A and B roads only (Supplemental Information 1).

Following this assessment of changes in absolute injury numbers, we assess likely changes in injury risk. For this we draw on previous work that estimates changes in levels of walking, cycling, and driving following the implementation of the LTNs.

FINDINGS

Inside the LTNs, injury numbers fell three-fold in the post period relative to the pre period (0.31 ratio relative to both Waltham Forest and Outer London, p<0.01, Table 1). Walking and cycling injury numbers fell two- to three-fold relative to both comparison groups (e.g. ratio 0.45, p=0.06, for numbers of pedestrian casualties relative to the rest of Waltham Forest). Numbers of car driver or passenger injuries decreased relative to both comparison groups (e.g. ratio 0.14, p<0.01, relative to the rest of Waltham Forest).

We did not identify any changes in injury numbers at the LTN boundaries (e.g. ratio 0.99 ratio for number of casualties travelling by any mode, p=0.94, relative to the rest of Waltham Forest (Table 2).

Analyses of KSI showed similar patterns both inside the LTNs and at the boundaries, but small numbers meant that power was extremely limited, and no changes were statistically significant. For example, the number of KSI fell from 7 pre to 3 post inside the LTNs, ratio 0.43, p=0.23, relative to the rest of Waltham Forest (Supplemental Information 1).

These analyses do not attempt to control for changes in travel patterns. Hence, they do not estimate risk to an individual, e.g. risk per trip. Inside the LTNs, survey evidence points to increased duration of walking (+29%) and cycling (+51%) by residents between 2016 and 2019 (see Aldred and Goodman 2020, and Supplemental Information 2). It is likely that the relative increase in active travel is even greater for travel inside the intervention area and so plausible that risk per hour travelled has reduced three- to four-fold for walking and cycling inside the LTNs.

Conversely, there were substantial reductions in motor vehicle traffic inside the LTNs. For example, traffic counts inside the 2015 LTN area indicate that the number of motor vehicle trips fell 56% from February 2014 to July 2016 (London Borough of Waltham Forest 2020). If this is typical, then the seven-fold reduction in numbers of car occupant injuries may approximately correspond to a four-fold reduction in risk per trip.

The trend at the LTN boundaries may also be more favourable on a per trip basis if these roads saw an increase in walking, cycling, and motorised travel. This is plausible for active travel given a) increased levels of walking and cycling among local residents in general and b) several boundary roads received walking and cycling interventions (e.g. new crossings and cycle tracks) in parallel to the LTNs. It is plausible for car travel given that, although there seems to have been substantial evaporation of motor traffic, some boundary roads did see an increase compared to years immediately before the interventions (London Borough of Waltham Forest 2020).

In summary, both absolute injury numbers and injury risk decreased substantially inside the LTNs. The estimated improvement in walking and cycling safety (three to four-fold for risk) would bring the UK into line with the best European countries (Castro, Kahlmeier, and Gotschi 2018). LTNs should be seen as an intervention that improves road safety as well as improving health through increased physical activity (see Aldred and Goodman 2020). Simultaneously intervening on boundary roads (e.g. building cycle tracks) may further enhance safety improvements.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

AL is funded by National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) School for Public Health Research.

.png)

.png)